Flour

about Flour: click here to read more

Flour has been part of the human diet for tens of thousands of years.

Archaeological findings show that Paleolithic hunter-gatherers were grinding wild seeds, grasses, and roots into a primitive form of flour as early as 30,000 BCE—long before agriculture began.

A grinding stone from Grotta Paglicci in southern Italy, for example, still contains starch residues from wild oats, evidence that early humans used flour-like substances to make primitive breads or porridges.

Around 10,000 BCE, with the rise of agriculture in the Fertile Crescent, humans began cultivating wheat, barley, and other cereals, which quickly became the main sources of flour.

Over the millennia, milling evolved—from stone hand tools to water and wind mills, and eventually to the industrial roller mills of the 19th century that made fine, white flour widely available.

Today, flour is made from an amazing range of plants: wheat, rye, barley, oats, rice, corn, millet, sorghum, teff, chickpeas, lentils, nuts, cassava, and more. Counting all regional and specialty flours, there are well over 100 types globally. Each culture not only favors certain grains but also classifies its flours differently—by chemical content, grind, or use—reflecting unique culinary traditions and milling practices.

🇫🇷🇮🇹🇺🇸 How Different Countries Classify Flour

France

Ash content (mineral residue after burning 100 g flour)

T45, T55, T65, T80, T110, T150

Lower number = whiter, finer flour. T45 used for pastries; T55 for baguettes; T80–T150 for rustic and wholegrain breads.

Italy

Grind fineness & protein content

00, 0, 1, 2, Integrale (wholemeal)

00 = most refined and softest (pasta, pastries); 0 = bread; 1 & 2 = coarser, more bran; Integrale = wholegrain.

United States

Intended use / gluten content

All-purpose, Bread, Cake, Pastry, Self-rising, Whole-wheat

All-purpose = general baking; Bread = high-gluten; Cake/Pastry = low-protein; Self-rising = with baking powder; Whole-wheat = wholegrain.

-

Chickpea (Garbanzo bean) Flour

Regular price $9.55 USDRegular priceUnit price / per$0.00 USDSale price $9.55 USD -

Essential Pantry Brown Teff Flour

Regular price $7.95 USDRegular priceUnit price / per$0.00 USDSale price $7.95 USD -

Whole Grain Emmer (Farro) Flour - Organic

Regular price $8.95 USDRegular priceUnit price / per$0.00 USDSale price $8.95 USD -

Caputo "00" Chefs Flour - 2.2 pounds

Regular price $8.95 USDRegular priceUnit price / per$0.00 USDSale price $8.95 USD -

Caputo Semolina Flour

Regular price $8.95 USDRegular priceUnit price / per$0.00 USDSale price $8.95 USD -

Caputo "00" Pizza Flour - 2 pounds

Regular price $8.95 USDRegular priceUnit price / per$0.00 USDSale price $8.95 USD -

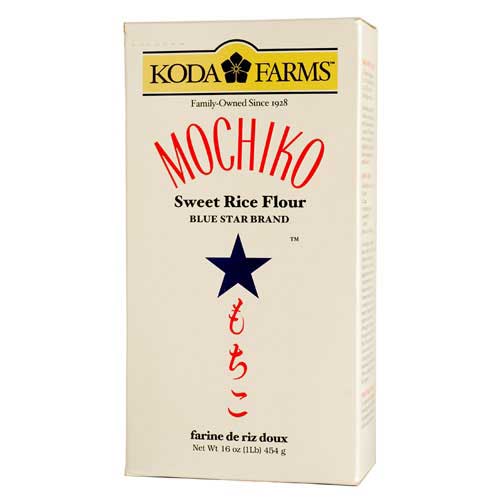

Sweet Rice Flour - Mochiko - 1 pound

Regular price $5.95 USDRegular priceUnit price / per$0.00 USDSale price $5.95 USD -

Erawan Brand Thai Rice Flour

Regular price $3.55 USDRegular priceUnit price / per$0.00 USDSale price $3.55 USD -

Moretti Semolina Flour

Regular price $7.95 USDRegular priceUnit price / per$0.00 USDSale price $7.95 USD -

Caputo Italian Gluten Free Flour

Regular price $21.95 USDRegular priceUnit price / per$0.00 USDSale price $21.95 USD -

Organic Golden Masa Harina (Corn Flour)

Regular price $10.95 USDRegular priceUnit price / per$0.00 USDSale price $10.95 USD -

Caputo 00 Pasta Flour - 2 pounds

Regular price $8.95 USDRegular priceUnit price / per$0.00 USDSale price $8.95 USD -

Shepherd's Grain Pastry Flour - 5 pound bag

Regular price $10.95 USDRegular priceUnit price / per$0.00 USDSale price $10.95 USD -

Shepherd's Grain Pastry Flour - 2 pounds

Regular price $6.95 USDRegular priceUnit price / per$0.00 USDSale price $6.95 USD -

Caputo 00 Pizza Flour - 5 pound bag

Regular price $17.95 USDRegular priceUnit price / per$0.00 USDSale price $17.95 USD -

Francine Fluide Lump-free T45 Flour

Regular price $7.55 USDRegular priceUnit price / per -

Restocking - choose Notify me

Restocking - choose Notify meTreblec French Buckwheat Flour

Regular price $11.95 USDRegular priceUnit price / per$0.00 USDSale price $11.95 USDRestocking - choose Notify me -

Restocking - choose Notify me

Restocking - choose Notify meErawan Brand Thai Glutinous Sweet Rice Flour

Regular price $3.45 USDRegular priceUnit price / per$0.00 USDSale price $3.45 USDRestocking - choose Notify me